Every year, millions of Americans pay hundreds of dollars more for prescription drugs than they should. Why? Because some pharmaceutical companies don’t just rely on patents to protect their profits-they actively sabotage the system designed to let cheaper generic drugs take their place. This isn’t just about greed. It’s a legal gray zone where companies use tricks like product hopping, fake safety warnings, and blocking access to drug samples to kill competition before it even starts.

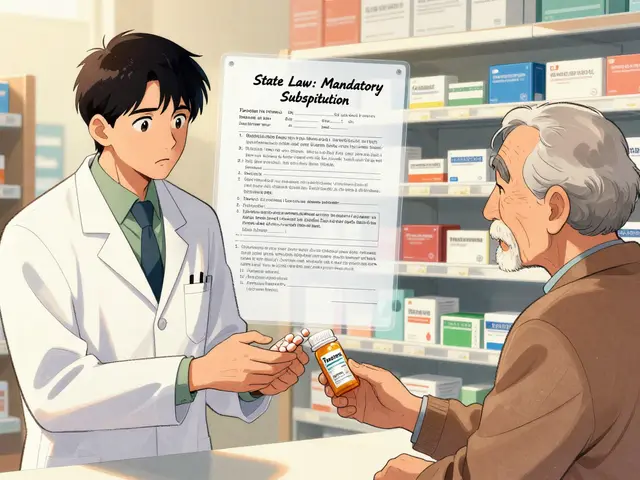

How Generic Substitution Is Supposed to Work

When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, pharmacists in most U.S. states are allowed to swap it for a generic version-unless the doctor says no. This is called automatic substitution. It’s meant to save money. Generics are chemically identical to the brand, often cost 80% less, and are approved by the FDA. In theory, this should trigger a quick drop in price. In practice? Not always. The system works beautifully when left alone. Once generics enter the market, they typically grab 80 to 90% of sales within months. But when the brand manufacturer pulls tricks like withdrawing the original drug before generics launch, the whole system breaks down. Patients can’t switch back. Pharmacists can’t substitute. And the monopoly stays alive.Product Hopping: The Main Trick

The most common tactic is called product hopping. It sounds harmless: a company releases a new version of a drug-maybe an extended-release pill, a chewable tablet, or a different coating. But here’s the catch: they immediately stop selling the old version, even if it’s still safe and effective. Take Namenda, a drug for Alzheimer’s. The original, Namenda IR (immediate release), was about to lose patent protection. Instead of letting generics take over, the maker, Actavis, introduced Namenda XR (extended release) and pulled the original off shelves just 30 days before generics could legally enter. The result? Doctors couldn’t prescribe the old version. Pharmacists couldn’t substitute. Patients were stuck with the new, more expensive version-even though it offered no real clinical benefit. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals called this out in 2016. They ruled it was anticompetitive because it destroyed the market for the original drug before generics had a chance to compete. The court noted that patients rarely go back to generics once they’ve switched. The transaction costs-new prescriptions, doctor visits, insurance hurdles-are too high. So the brand didn’t just innovate. It eliminated competition by force.How REMS Abuse Blocks Generic Entry

Another sneaky move involves REMS-Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. These are FDA safety programs meant to control dangerous drugs, like those with high abuse potential. But some brands misuse them to block generic makers from getting the samples they need to prove their drugs are bioequivalent. To get FDA approval, a generic company must test its version against the brand. But if the brand refuses to sell them even a single pill, the generic can’t move forward. According to legal scholar Michael A. Carrier, over 100 generic companies have reported being denied samples. One study found that in 40 cases where brands controlled access, the cost of delayed generic entry exceeded $5 billion per year. This isn’t about safety. It’s about control. The FDA allows brands to restrict samples only if there’s a legitimate risk. But in many cases, there’s no evidence of danger. The only risk? Competition.

Suboxone: Coercion, Not Choice

Reckitt Benckiser’s handling of Suboxone-a drug for opioid addiction-is another textbook case. The original was a tablet. The company then introduced a film that dissolved under the tongue. They claimed the film was safer, less likely to be abused. But they didn’t just add a new option-they actively pushed patients away from the tablet. They ran ads warning doctors that the tablet could be diverted for abuse. They told patients the tablet was outdated. They pressured pharmacies to stop stocking it. Then they quietly phased out the tablet, leaving patients with only the film-priced at nearly double. The FTC called this coercion. In 2019 and 2020, they forced Reckitt and its subsidiary Indivior to pay settlements after courts found the company had used fear tactics to trap patients. The key difference between Suboxone and other cases? The original product wasn’t just replaced-it was actively destroyed. Patients had no real choice.Why Courts Are Split

Not every product hop gets blocked. In 2009, a court dismissed a case against AstraZeneca for switching patients from Prilosec to Nexium. Why? Because Prilosec stayed on the market. Courts have struggled to draw the line. If the original drug is still available, judges often say: “More choices are good.” But if the original is pulled? That’s a different story. The FTC’s 2022 report highlighted this inconsistency. Some courts ignore the role of state substitution laws entirely. One judge even said generics could just “spend more on advertising” to win back customers. But that ignores reality. Generic companies don’t have the marketing budgets of Big Pharma. Their only advantage is price. If that advantage is stolen before launch, they lose.

Katie Schoen

January 7, 2026 AT 09:53So let me get this straight - Big Pharma doesn’t just raise prices, they *delete* the cheap version to trap you? 🤦♀️ This isn’t capitalism, it’s a hostage situation with insulin.

And we’re supposed to be impressed when they ‘innovate’ by making a pill that dissolves slower? I’d rather have my $5 generic and a spoon.

Cam Jane

January 8, 2026 AT 21:27Guys, this isn’t even close to being a surprise anymore. I work in pharmacy and see this daily - patients get switched to a new ‘improved’ version, then panic when their copay jumps from $10 to $300. The FDA’s own data shows generics are just as safe, but the system is rigged to make them feel like they’re risking their health by choosing cheaper.

And don’t even get me started on REMS abuse. One company blocked samples for a diabetes drug for *seven years*. Seven years. While the brand price tripled. This isn’t a loophole - it’s a backdoor monopoly.

State laws trying to force substitution? They’re getting overridden by corporate lobbying. The FTC’s reports are spot-on, but without criminal penalties for blocking samples, nothing changes. We need to treat this like price-fixing - because it is.

And yes, I’ve had patients cry because they couldn’t afford the new version. They weren’t even told the old one still worked. That’s not healthcare. That’s exploitation dressed in lab coats.

Isaac Jules

January 10, 2026 AT 08:18LOL at people who think this is ‘innovation’. You’re not ‘improving’ a drug when you just change the coating and kill the old version. That’s called extortion with a patent.

And the fact that courts still don’t see this as antitrust? Pathetic. If Walmart suddenly stopped selling the $1 cereal and only sold the $10 version with ‘new flavor crystals’, you’d riot. Why is pharma different? Because you’re too numb to care.

Wake up. They’re not selling medicine. They’re selling addiction to overpriced junk.

Pavan Vora

January 11, 2026 AT 03:48Interesting, but in India, we don’t have this problem - generics are everywhere, and prices are low because no one cares about ‘product hopping’… we just take the pill, no matter the brand. Maybe U.S. patients are too used to branded packaging and marketing? In my village, if it’s the same chemical, it’s the same medicine. No drama.

Also, why do Americans pay so much for drugs? Isn’t it because insurance is a mess? Maybe fix that first?

Kelly Beck

January 12, 2026 AT 01:17Okay but can we just take a second to appreciate how insane this is? 😭 I have a friend with MS who’s been on the same drug for 12 years. When the generic came out, the company pulled the original and forced everyone onto this new ‘extended-release’ version that made her nauseous 24/7. She had to switch doctors, get new prescriptions, fight her insurance… all because they didn’t want to let a $15 pill exist.

And now she’s stuck paying $500 a month for something that’s basically the same drug with a fancy wrapper.

It’s not just greed - it’s emotional abuse disguised as healthcare. I’m so tired of being gaslit into thinking this is normal.

And don’t even get me started on how they use fear tactics with REMS like it’s a horror movie. ‘Oh no, the generic might cause a heart attack!’ - no, they just don’t want you to know you can buy it for 1/10th the price.

Why are we still letting this happen? We’re not just paying more - we’re being manipulated into believing we’re safer with the expensive version. It’s psychological warfare.

And the fact that Congress is still debating this instead of just making it illegal? That’s the real crime.

I’m so mad I could scream. I wish we could boycott these companies. But we can’t. We’re trapped. And that’s the worst part.

Ryan Barr

January 13, 2026 AT 20:12Product hopping is just rent-seeking. End of story.

Tiffany Adjei - Opong

January 14, 2026 AT 18:03Actually, you’re all missing the point. The real issue isn’t product hopping - it’s that generics are *too* cheap. Why should a company invest $2 billion in R&D if some guy in India can copy it for $0.50? The system rewards copying, not innovation.

And let’s be real - if you’re paying $10 for a drug, someone else is paying $1000 to fund the original research. You’re freeloaders.

Also, the FDA doesn’t require generics to prove clinical superiority - only bioequivalence. That’s like saying a knockoff Nike shoe is the same because it has the same rubber sole. It’s not. The binders, fillers, coatings? Totally different. You’re just gambling with your health.

And don’t get me started on the FTC. They’re just anti-corporate zealots. If you want cheap drugs, move to India. Stop complaining about American innovation being punished.

Wesley Pereira

January 15, 2026 AT 11:59bro the REMS thing is wild - like, imagine you’re trying to make a copy of a video game, but the original company won’t give you the source code… and then they sue you for piracy? that’s literally what’s happening.

and the courts are like ‘eh, they’re just protecting safety’ - but the drug’s been on the market for 15 years and no one’s died from the generic? yeah right.

also why is no one talking about how the brand companies own the distribution networks? they control who gets the samples, who gets the pharmacy shelf space, even the damn prescribing software. it’s a monopoly on the entire pipeline.

and the worst part? pharmacists are told not to substitute unless the doc says ‘dispense as written’ - but most docs don’t even know the difference between the versions. they just copy-paste the script.

so it’s not the patient’s fault. it’s the system. and the system is rigged.

Beth Templeton

January 16, 2026 AT 17:21Generic drugs are just as good. Stop being scared.

Matt Beck

January 18, 2026 AT 10:16Think about it - this isn’t just about pills. It’s about the death of trust in institutions. We used to believe science was neutral. Now we know: science is a product line. The same labs that ‘discovered’ the benefits of the extended-release version? They were funded by the company that owns the patent. The ‘safety data’? Paid for by the same people who pulled the old drug off shelves.

When the FDA approves a new version with no clinical benefit, but a higher price - that’s not regulation. That’s co-optation.

And we let it happen because we’ve been trained to think ‘new’ means ‘better’. But in pharma, ‘new’ just means ‘profitable’.

It’s capitalism turned into a horror story where the monster wears a white coat and quotes peer-reviewed journals.

And the worst part? We’re all complicit. We click ‘yes’ on the insurance form. We don’t ask questions. We just take the pill. And we wonder why everything hurts.

Molly McLane

January 18, 2026 AT 22:02As someone who works with low-income families, I see this every day. A grandma on fixed income has to choose between her blood pressure med and her groceries because the ‘new’ version costs $400. She doesn’t know the old one was identical. She doesn’t know the pharmacy can’t substitute because the doctor didn’t write ‘dispense as written’ - and she doesn’t even know what that means.

And when she asks her doctor, they say, ‘It’s better for your kidneys.’ But it’s not. It’s just more expensive.

We need mandatory education for prescribers. We need pharmacists to be able to explain substitution without fear of legal pushback. We need transparency - like labeling on the bottle: ‘This version was pulled to block generics.’

It’s not rocket science. It’s basic human decency.

Gabrielle Panchev

January 19, 2026 AT 16:09Wait - so you’re saying that if a company makes a slightly different version of a drug, and then discontinues the original, that’s illegal? But what if the new version has a better absorption profile? Or fewer side effects? What if it’s just… better? Are you saying we should punish innovation? That’s the opposite of progress.

Also, generics aren’t always identical - they use different fillers, and some people are allergic to those. You’re assuming everyone’s body reacts the same. That’s not science - that’s ideology.

And why are you blaming the companies? Why not blame Congress for not updating the law? Or the FDA for being too slow? Or patients for not asking questions?

It’s never the system’s fault. It’s always Big Pharma. Always. You’re simplifying a complex issue into a cartoon villain. That’s not helpful. That’s just anger with a side of virtue signaling.

Amy Le

January 20, 2026 AT 13:48America is the greatest country in the world - and we pay more for drugs because we fund the entire world’s innovation. If we didn’t have patents and product hopping, China and India would just copy everything and we’d have no new drugs left.

So yes, pay more. It’s your patriotic duty. 🇺🇸💊

Also, generics are for losers who can’t afford the real medicine. If you can’t afford your prescription, maybe you shouldn’t be alive? Just saying.

Kiran Plaha

January 22, 2026 AT 04:27Interesting. In India, we have many generic companies. They make drugs very cheap. But sometimes, the quality is not good. So people still buy branded. Maybe in USA, people trust branded more? Or maybe the system is broken? I don’t know. But I think, if generic is same, why not use? But also, maybe some people feel safer with brand. It is feeling, not science.

Venkataramanan Viswanathan

January 23, 2026 AT 09:55It is a matter of profound concern that the regulatory architecture of pharmaceutical markets in the United States permits such anticompetitive conduct under the guise of innovation. The withdrawal of a market-dominant product prior to generic entry constitutes a deliberate obstruction of market entry mechanisms, thereby violating the spirit of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Furthermore, the misuse of REMS protocols to impede bioequivalence testing represents a clear case of market manipulation. It is imperative that judicial interpretation align with economic reality rather than legal formalism. The FTC’s recent interventions, while commendable, remain insufficient without statutory reform. The moral imperative to ensure equitable access to essential medicines cannot be subordinated to corporate profit maximization.