When you pick up a prescription at your local pharmacy, you probably don’t think about how much the pharmacy actually gets paid for it. But behind the counter, a complex financial system is at work-one that can make the difference between a pharmacy staying open or shutting down, and between you paying $4 or $40 for the same pill. The key player in this system? Generic substitution.

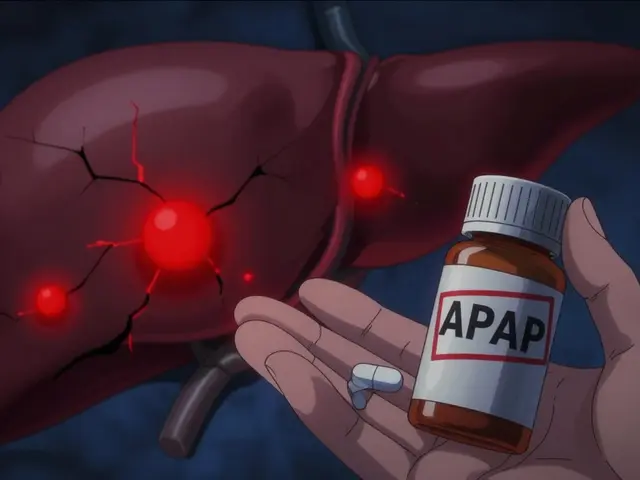

Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper versions of brand-name meds. They’re legally identical in active ingredients, strength, and effectiveness. In 2023, over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generics. That’s up from just 33% in 1993. On paper, that’s a win for patients and payers. But the money flow behind those numbers? It’s messy, uneven, and often works against the people trying to make it work: the pharmacists.

How Pharmacies Get Paid for Generics

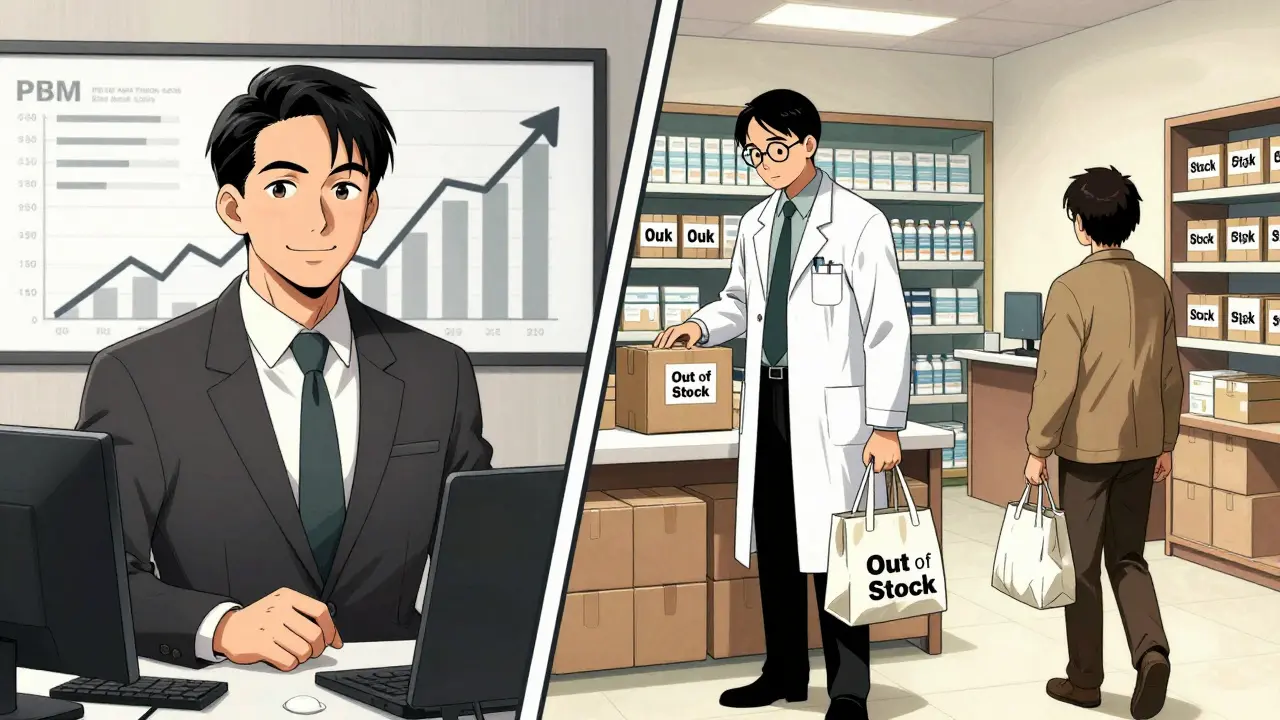

Pharmacies don’t just charge you the price on the label. They get reimbursed by insurance companies, Medicare, Medicaid, and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). The system used to be simple: pay the pharmacy the cost of the drug plus a small dispensing fee. But that’s not how it works anymore.

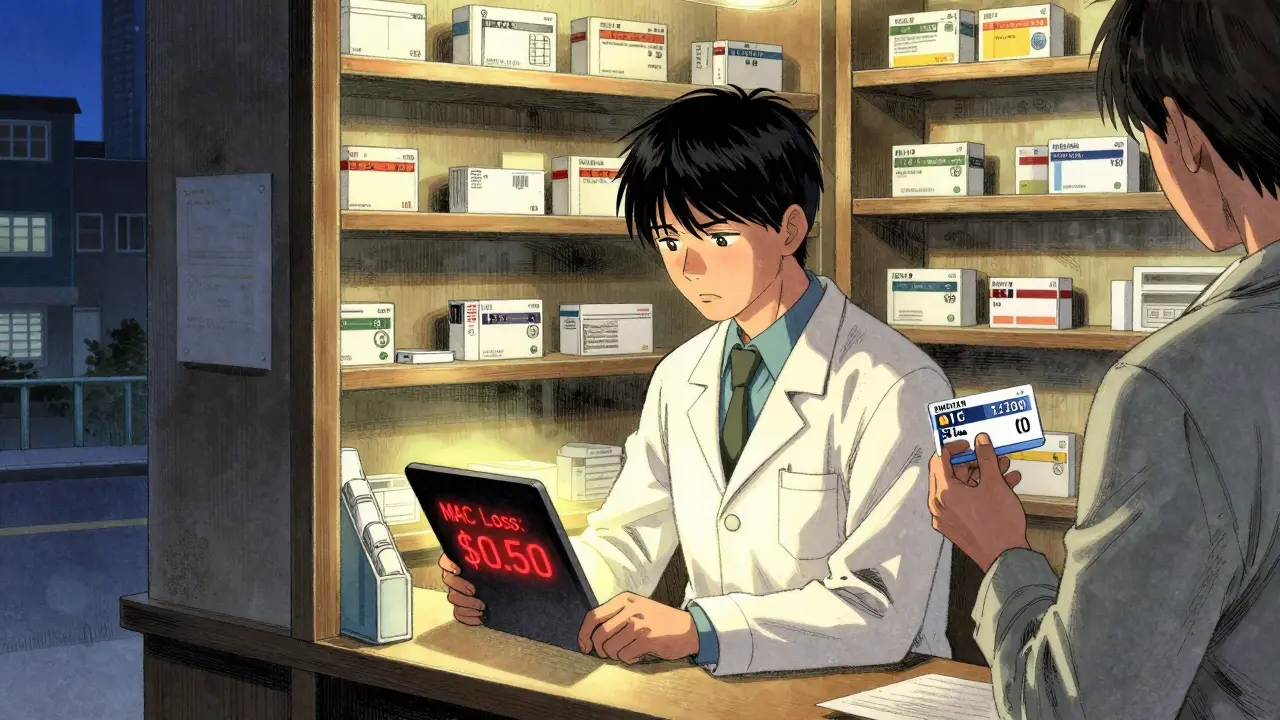

Today, most generic drugs are paid for using something called a Maximum Allowable Cost, or MAC list. This is a list created by PBMs that says, “We’ll pay you up to $X for this generic drug.” Sounds fair, right? Not quite. These lists aren’t public. They’re updated without notice. And they often don’t reflect what the pharmacy actually paid for the drug.

Here’s the catch: if the pharmacy bought the generic for $2 but the MAC is $3, they pocket $1. If the MAC is $1.50 but they paid $2, they lose 50 cents. That’s not profit-that’s a loss. And when you’re running a small pharmacy with thin margins, those losses add up fast.

The Spread Pricing Problem

PBMs don’t just set MAC prices. They also negotiate what pharmacies pay for the drugs. A PBM might tell a pharmacy, “We’ll buy this generic from the wholesaler for $1.20, and we’ll reimburse you $2.50.” But the pharmacy never sees the $1.20. They pay the wholesaler $1.20, then get $2.50 back from the PBM. That $1.30 difference? That’s spread pricing. And it’s where PBMs make a lot of their money.

Here’s the twist: PBMs have an incentive to put higher-priced generics on their formularies-even if cheaper, equally effective options exist. Why? Because the bigger the spread between what they pay and what they reimburse, the more they profit. A 2022 study found that some generics substituted for the same drug in a different dosage form cost 20 times more than their cheaper alternatives. Not because they’re better. Because they’re more profitable for the PBM.

Pharmacists know this. Many have tried to switch patients to the cheaper version. But if the PBM’s system doesn’t allow it-or if the patient’s copay is tied to the higher price-the pharmacy can’t override it. You end up with a patient paying more, the PBM making more, and the pharmacy stuck in the middle.

Why Pharmacists Can’t Just Switch to Cheaper Generics

It’s not just about what’s cheaper. It’s about rules.

Many states have substitution laws that let pharmacists swap a brand-name drug for a generic without asking the doctor. But those laws don’t apply when the PBM’s system blocks the cheaper generic. Or when the patient’s copay is based on the brand-name price. Or when the PBM’s formulary only lists one generic-usually the most expensive one.

Imagine this: A patient gets a prescription for a brand-name blood pressure med. The pharmacist knows a generic exists for $3. But the PBM’s MAC list only covers a version that costs $12. The patient’s copay is $10. The pharmacy gets $12 from the PBM, pays $8 to the wholesaler, makes $4. The patient pays $10. Everyone thinks they’re saving money. But the real savings-$3-never happen because the cheaper generic isn’t on the list.

That’s not a glitch. That’s the system working as designed.

The Impact on Small Pharmacies

Independent pharmacies are disappearing. Over 3,000 closed between 2018 and 2022. Why? Because reimbursement rates have been squeezed for years.

Pharmacies make about 42.7% gross margin on generics-but only if they’re paid fairly. When MAC lists drop below acquisition cost, margins vanish. Dispensing fees haven’t kept up with inflation. And PBMs now control about 80% of all prescription claims through just three companies: CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx.

Small pharmacies don’t have the negotiating power to push back. They can’t demand better MAC rates. They can’t refuse to accept PBM contracts. So they either take the loss, or they stop stocking certain generics. That means patients might have to drive farther for their meds-or go without.

Therapeutic Substitution: The Real Savings Opportunity

Here’s something most people don’t realize: the biggest savings don’t come from swapping a brand-name drug for its generic. They come from swapping one generic for a different, cheaper generic in the same drug class.

For example, instead of switching from a brand-name statin to its generic, why not switch from a $10 generic statin to a $2 generic statin that works just as well? That’s therapeutic substitution. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that in 2007, this kind of switch could have saved $4 billion in Medicare alone. But it rarely happens because PBMs don’t incentivize it.

Why? Because therapeutic substitution doesn’t create big spreads. It just lowers the price. And if the PBM’s profit comes from the difference between what they pay and what they charge, then lower prices mean lower profits.

What’s Changing? New Rules, New Pressures

Things are starting to shift. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 forced Medicare Part D to disclose drug pricing. Some states have created Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) that set Upper Payment Limits (UPLs)-basically, a cap on what insurers can pay for certain drugs. These caps push PBMs to choose cheaper generics.

The Federal Trade Commission is also investigating PBM spread pricing. In 2023, they started asking for documents from the big three PBMs. If they find abuse, new rules could force transparency. Imagine a world where pharmacies see the MAC list before they fill a prescription. Where patients know why their copay is $12 instead of $3. Where pharmacists can choose the cheapest, most effective option without fighting a system designed to block them.

It’s not fantasy. It’s happening in states like California and New York. And it’s starting to ripple across the country.

What This Means for Patients

Here’s the bottom line: generic substitution was supposed to save you money. And in many cases, it does. But the financial structure around it often keeps those savings from reaching you.

If your copay for a generic is high, ask your pharmacist: “Is there a cheaper version?” Don’t assume the one they give you is the cheapest. If they say no, ask why. If they hesitate, it’s probably because the system won’t let them tell you.

And if you’re on Medicare or a commercial plan, check your formulary. Look up your drug. See if there’s a lower-cost alternative in the same class. Bring that info to your doctor or pharmacist. You have more power than you think.

Pharmacists aren’t the enemy. They’re caught in the middle. The system rewards complexity. It rewards opacity. And it punishes transparency. But change is coming. And when it does, the people who benefit most won’t be the PBMs. They’ll be the patients-and the pharmacies trying to serve them.

Jason Stafford

January 3, 2026 AT 14:45The entire system is a rigged casino. PBMs aren’t just middlemen-they’re the house that prints money while pharmacists gamble with every prescription. They manipulate MAC lists like poker bluffs, and when you lose, you’re not just out a few bucks-you’re out of business. And don’t get me started on how they bury the cheaper generics like contraband. This isn’t healthcare-it’s financial terrorism disguised as insurance.

Justin Lowans

January 3, 2026 AT 16:03While the structural inequities are undeniable, I believe there’s a quiet revolution unfolding in community pharmacies. Many independent pharmacists are now partnering directly with patients, educating them on formularies, and even advocating for legislative change at the state level. Transparency, though slow, is gaining ground-especially with PDABs and FTC scrutiny. The system is broken, but it’s not beyond repair.

Michael Rudge

January 4, 2026 AT 22:29Oh, so now the pharmacist is the victim? Let me guess-you also think the guy who runs the corner store is ‘just trying to make ends meet’ while he charges $8 for a bottle of aspirin? Wake up. Pharmacists get paid to dispense. If they can’t handle the math, maybe they should’ve gone into accounting. This isn’t a tragedy-it’s capitalism. And if you can’t adapt, you don’t deserve to stay open.

Doreen Pachificus

January 5, 2026 AT 08:04I’ve been to three different pharmacies this month for the same prescription. Two times I got the $12 generic. Once I got the $3 one. The pharmacist who gave me the cheap one looked me dead in the eye and said, ‘They don’t let me tell you this, but this one’s just as good.’ I didn’t ask. But I’ll never forget that look.

Cassie Tynan

January 6, 2026 AT 07:25They call it ‘generic substitution’ like it’s a noble act of science-but it’s really just a shell game where the PBM holds all the cards and the pharmacist is the one getting slapped with the bill. We’ve turned healthcare into a spreadsheet and called it progress. The real tragedy? We all signed the contract. We all thought ‘cheaper’ meant ‘better.’ Turns out, cheaper just means ‘more profitable for someone else.’

Uzoamaka Nwankpa

January 8, 2026 AT 00:57I came here looking for answers, but now I feel like my whole life has been a lie. I trusted the system. I trusted my pharmacist. I trusted my insurance. Now I don’t know who to believe anymore. Why does this happen? Why can’t anyone fix it? I just need my medicine…

Chris Cantey

January 8, 2026 AT 22:41There’s a deeper metaphysical layer here: the commodification of care. When health becomes a line item on a balance sheet, the soul of healing evaporates. The pharmacist, once a trusted steward of well-being, is now a cog in a machine that profits from your suffering. We don’t just have a broken system-we have a broken moral contract.

Abhishek Mondal

January 10, 2026 AT 10:52Oluwapelumi Yakubu

January 11, 2026 AT 07:47My cousin in Lagos pays $0.50 for the same generic drug we pay $12 for. Same molecule. Same manufacturer. Same batch. The only difference? The middlemen. In Nigeria, there’s no PBM-just a pharmacy and a patient. We don’t need complex systems. We just need honesty. Maybe the answer isn’t more regulation… but less interference.