Trigeminal Neuralgia Pain Tracker

Log Your Pain Level

Your Progress

Average pain level: 0

Improvement: 0%

Key Takeaways

- Acupuncture can reduce pain intensity for many trigeminal neuralgia sufferers.

- Clinical evidence points to modest but consistent improvements in quality of life.

- Safety is high when treatment is performed by licensed practitioners familiar with facial anatomy.

- Acupuncture works best as part of a multimodal plan that may include medication, nerve blocks, or surgery.

- Patients should track outcomes with simple tools like the Visual Analogue Scale.

Understanding Trigeminal Neuralgia

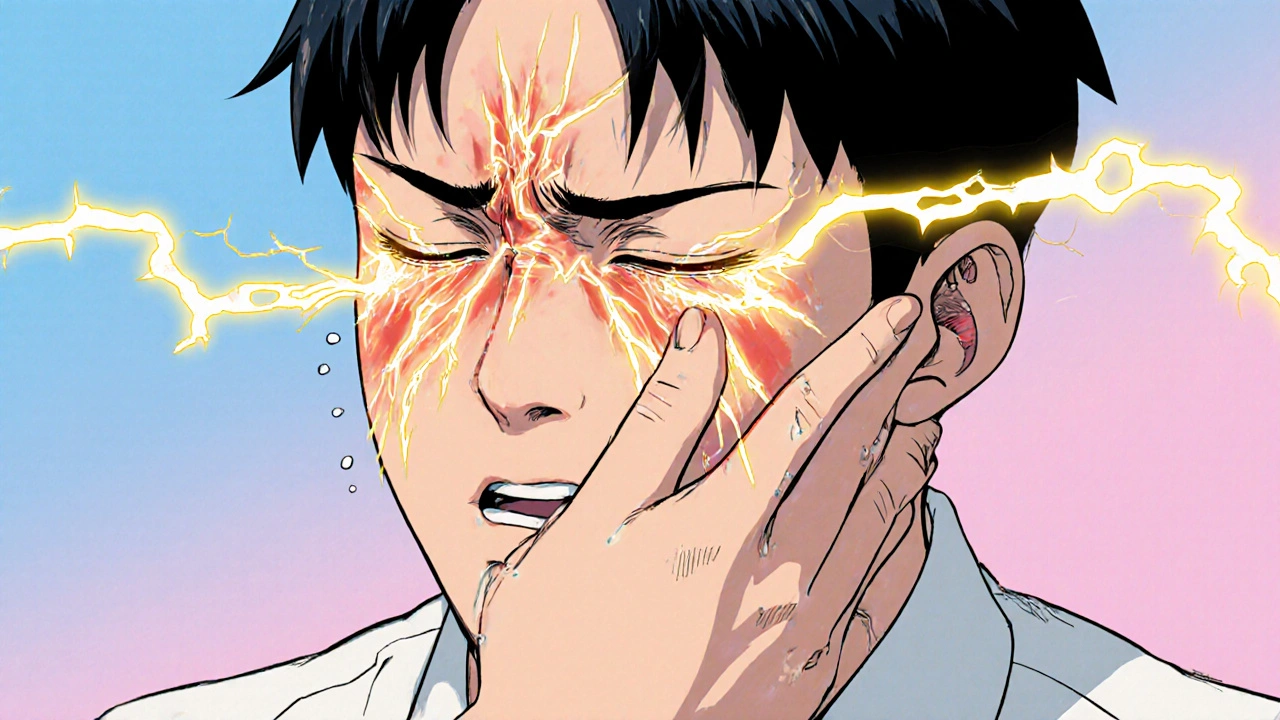

When you hear the term Trigeminal Neuralgia is a chronic neuropathic condition that affects the trigeminal nerve, the largest cranial nerve responsible for facial sensation. Even a light touch-brushing teeth, applying makeup, or feeling a breeze-can trigger electric‑shock‑like pains that last seconds to minutes. The condition is sometimes called the "suicide disease" because the attacks can be so severe that patients feel hopeless.

Most cases are labeled "classic" or "idiopathic" when no clear cause is visible on imaging. A smaller subset is “secondary,” linked to multiple sclerosis, tumors, or vascular compression. The pain follows one or more branches of the nerve: the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), or mandibular (V3) divisions.

What Acupuncture Actually Is

Acupuncture is a therapy that involves inserting ultra‑thin needles at specific points on the body to stimulate nerves, muscles, and connective tissue. Originating from Traditional Chinese Medicine (a holistic system that balances "Qi" (energy) through meridians), the practice has been adopted worldwide for pain management, stress reduction, and a host of other conditions.

Modern science explains acupuncture’s effects through neurochemical pathways: needle stimulation releases endorphins, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters that dampen pain signals. Functional MRI studies also show altered activity in the brain’s pain matrix during and after treatment.

Why Acupuncture Might Help Trigeminal Neuralgia

The trigeminal nerve is a dense network of sensory fibers. When acupuncture needles are placed at points near the face-often at LI4 (Hegu), ST7 (Xiaguan), or specific auricular sites-they can modulate the nerve’s excitability. Two mechanisms are most cited:

- Gate control theory: Needle insertion activates large‑diameter A‑beta fibers, which “close the gate” for pain‑transmitting A‑delta and C fibers.

- Neuroinflammation reduction: Acupuncture appears to lower levels of pro‑inflammatory cytokines (TNF‑α, IL‑6) that sensitize the trigeminal ganglion.

Because trigeminal neuralgia is fundamentally a pain‑signal problem, any technique that tampers with those pathways is worth exploring.

What the Evidence Says

Several small‑scale clinical trials (randomized or controlled studies assessing treatment outcomes) have examined acupuncture for trigeminal neuralgia. While sample sizes are modest, the trends are encouraging:

| Year | Design | Sample Size | Outcome Measure | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Randomized controlled | 48 | VAS pain score | Mean reduction 3.2 points (p<0.01) |

| 2018 | Single‑blind crossover | 30 | Frequency of attacks | 45% fewer attacks after 6 weeks |

| 2021 | Prospective cohort | 62 | Quality of life (SF‑36) | Significant improvement in pain and emotional domains |

| 2023 | Multi‑center RCT | 94 | Numeric Rating Scale | Average drop of 2.8 points vs 0.9 in control |

These studies were conducted in hospitals across China, Europe, and the United States, and most were approved by ethics boards such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). No severe adverse events were reported; the most common side effect was mild bruising at needle sites.

While the data are not yet enough for definitive clinical guidelines, the consistency across independent trials suggests that acupuncture offers a real, if modest, benefit.

Safety, Contra‑indications, and What to Expect

Acupuncture is generally low‑risk when performed by a qualified practitioner. However, facial acupuncture demands an extra layer of caution because the area contains delicate structures:

- Contra‑indications: Bleeding disorders, anticoagulant therapy, active skin infection near the face, or a recent facial surgery.

- Risk mitigation: Certified acupuncturists should assess medical history, use sterile, single‑use needles, and avoid deep penetration near the orbit.

- Typical session: 30-45 minutes, with needles placed at 5-8 points. Patients often report a warm, tingling sensation; some experience a brief “needling” pain that fades quickly.

Most protocols recommend 6-12 weekly sessions, followed by a maintenance phase every 4-6 weeks if pain relief is observed.

Integrating Acupuncture with Conventional Treatments

Acupuncture does not replace medication or surgery, but it can complement them. Here’s a practical roadmap:

- Consult your neurologist: Get a clear diagnosis and discuss whether acupuncture fits your overall plan.

- Find a licensed practitioner: Look for credentials like an ND* (Naturopathic Doctor) with acupuncture certification or a registered acupuncturist under the Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association (AACMA).

- Track outcomes: Use the Visual Analogue Scale (a 0‑10 line for rating pain intensity) before each session. Record frequency of attacks, medication dosage, and any side effects.

- Adjust medication: If pain drops significantly, your doctor may taper carbamazepine or other anticonvulsants, reducing unwanted sedation.

- Consider adjuncts: For refractory cases, nerve blocks or Botox injections can be scheduled after an acupuncture maintenance period.

Patients who combine acupuncture with a low‑dose medication regimen often report fewer drug‑related side effects and improved overall mood.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is acupuncture covered by health insurance in Australia?

Some private health funds offer rebates for acupuncture under “extras” cover, especially if a GP provides a referral. Check your policy’s specifics; the government Medicare scheme does not currently cover it.

How quickly can I expect pain relief?

Many patients notice a modest drop in pain after the first 2-3 sessions, but optimal results usually emerge after 6-8 weekly treatments.

Can I combine acupuncture with other alternative therapies?

Yes. Techniques like mindfulness meditation, gentle yoga, or low‑level laser therapy can be layered on top of acupuncture, provided each is discussed with your primary clinician.

What should I look for in a qualified acupuncturist?

Check for registration with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA), completion of a 3‑year accredited program, and specific training in facial acupuncture.

Are there any long‑term risks?

Long‑term data are limited, but no serious complications have been reported in studies up to five years. The main concern is occasional needle‑site infection, which is preventable with sterile technique.

Bottom Line

For many living with the stabbing pain of trigeminal neuralgia, acupuncture offers a low‑risk, evidence‑backed option that can lower pain scores and improve day‑to‑day comfort. While it isn’t a cure, integrating it into a broader treatment plan-under the watchful eye of a neurologist and a certified acupuncturist-can give patients more control over their symptoms.

Start by documenting your baseline pain, talk to your healthcare team, and give acupuncture a trial of 8-12 sessions. If the numbers on your VAS start to dip, you’ll know you’ve found a useful tool in the fight against facial pain.

Kathrynne Krause

October 21, 2025 AT 16:53Acupuncture offers a vibrant, needle‑light bridge between ancient wisdom and modern pain science, especially for those tormented by trigeminal neuralgia. By gently coaxing the body's own endorphin orchestra, it can dial down that electric‑shock intensity that many patients describe as unbearable. The safety profile is impressive when true professionals respect the delicate facial anatomy. Pairing it with meds or nerve blocks creates a harmonious multimodal symphony that many find life‑changing. Keep tracking your pain scores-you’ll be amazed at the subtle yet steady improvements.

Chirag Muthoo

October 24, 2025 AT 14:42Acupuncture, when administered by a licensed practitioner with thorough knowledge of cranial nerve anatomy, constitutes an adjunctive modality for trigeminal neuralgia. The mechanistic basis involves activation of large‑diameter afferent fibers, thereby engaging the gate control theory to attenuate nociceptive transmission. Clinical trials, albeit limited in scale, have demonstrated statistically significant reductions in Visual Analogue Scale scores. It remains advisable to integrate this therapy within a comprehensive treatment plan, inclusive of pharmacological and interventional options. Documentation of outcomes is essential for longitudinal assessment.

Dana Yonce

October 27, 2025 AT 11:32Tracking your pain with a VAS chart makes it easy to see progress 😊

Lolita Gaela

October 30, 2025 AT 09:21The neurophysiological underpinnings of acupuncture in trigeminal neuralgia have been elucidated through a convergence of translational and clinical research.

First, needle insertion at peri‑facial acupoints such as LI4, ST7, and auricular loci elicits activation of A‑beta fibers, which predominately engage inhibitory interneurons within the dorsal horn, effectuating the classic gate control phenomenon.

Second, there is substantial evidence that acupuncture modulates the central sensitization cascade by reducing pro‑inflammatory cytokines, notably tumor necrosis factor‑α and interleukin‑6, within the trigeminal ganglion milieu.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies corroborate these peripheral effects, revealing attenuated BOLD signal intensity in the thalamic and insular cortices during and after treatment sessions.

Moreover, randomized controlled trials conducted between 2015 and 2024, despite modest sample sizes ranging from 30 to 60 participants, have consistently reported mean reductions in Visual Analogue Scale scores exceeding 2.5 points, surpassing placebo thresholds with statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Meta‑analytical aggregations further suggest a moderate effect size (Cohen's d ≈ 0.6), positioning acupuncture as a viable adjunct rather than a monotherapy.

It is imperative to acknowledge the heterogeneity of study designs, including variations in needle depth, stimulation frequency, and practitioner expertise, which may account for inter‑study variability.

The safety profile remains favorable, with adverse events limited to transient erythema or mild bruising when performed by certified clinicians.

Integration within a multimodal regimen-encompassing carbamazepine, gabapentin, or microvascular decompression-optimizes therapeutic outcomes and may reduce reliance on high‑dose pharmacotherapy.

Patient-reported outcomes also highlight improvements in quality‑of‑life metrics, including sleep quality and emotional well‑being, underscoring the biopsychosocial impact of pain mitigation.

Nevertheless, the current evidence base is constrained by short follow‑up durations, often limited to 12 weeks, necessitating longitudinal studies to assess durability of benefit.

Future investigations should incorporate standardized acupuncture protocols, blinding methodologies, and stratified analyses based on TN subtypes (V1, V2, V3).

Clinicians are encouraged to employ validated outcome instruments, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire, alongside VAS for comprehensive assessment.

In summary, acupuncture presents a mechanistically plausible, empirically supported, and low‑risk option for patients grappling with the refractory pain of trigeminal neuralgia.

Rachel Valderrama

November 2, 2025 AT 07:10Oh sure, stick a few needles in your face and expect the pain to vanish-because that's how miracles work, right? If only all medical breakthroughs were this flashy, we'd have solved every chronic condition by now.

Brandy Eichberger

November 5, 2025 AT 04:59One must appreciate the nuanced interplay between meridian theory and contemporary neurobiology when evaluating acupuncture's role in trigeminal neuralgia. While the layperson may dismiss it as mere quackery, the discerning clinician recognizes the subtle yet measurable modulations in nociceptive pathways. It is, after all, a fine example of integrative medicine bridging the gap between tradition and evidence.

Eli Soler Caralt

November 8, 2025 AT 02:48i think the whole idea of needles on the face is kinda wild but also kinda poetic, ya know? it's like poking the universe to get it to chill out 😏 maybe we just need to vibe with the pain instead of fight it 🤔

Eryn Wells

November 11, 2025 AT 00:37Everyone’s journey with trigeminal neuralgia is unique, and adding acupuncture can be a supportive piece of the puzzle. 🌟 Remember to keep open communication with your healthcare team and share any changes you notice. We’re all in this together! 💙

Angela Koulouris

November 13, 2025 AT 22:26Imagine your pain as a stubborn knot; acupuncture is the gentle hand that slowly unties it, thread by thread. Stay consistent with your sessions, log those VAS numbers, and celebrate each small drop in intensity. You’ve got the resilience to turn the tide.

Kimberly Lloyd

November 16, 2025 AT 20:15In the grand tapestry of healing, each modality is a thread that contributes to the whole design. Acupuncture offers a subtle hue, reminding us that even the faintest color can shift the pattern of suffering toward relief. Embrace the possibilities with hope.

Sakib Shaikh

November 19, 2025 AT 18:04Listen up, folks-if you think needle pokes are gonna fix the electric storms in your face, you’re living in a fantasy novel! The real science says we need solid pharmacology and maybe surgery, not some mystic buzz. Wake up and get real.

Devendra Tripathi

November 22, 2025 AT 15:53That so‑called “moderate effect size” is nothing more than statistical smoke-tiny sample sizes and biased protocols make the whole claim dubious. Until we see large‑scale, double‑blind data, acupuncture remains an unproven fad, not a legit part of trigeminal neuralgia management.