Switching from a brand-name NTI drug to a generic version sounds simple: same active ingredient, lower cost, right? But for drugs with a Narrow Therapeutic Index, that small change can have big consequences. NTI drugs are the kind where a tiny difference in blood levels - even 10% - can mean the difference between effective treatment and serious harm. Think seizures, blood clots, organ rejection, or even death. And yet, across the U.S. and beyond, these switches happen every day. So what do the real-world studies actually show?

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

NTI stands for Narrow Therapeutic Index. These are medications where the gap between a safe dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. The FDA defines them as drugs where small changes in blood concentration can cause life-threatening failures or permanent disability. That’s not theoretical - it’s measurable. For most drugs, a 20% drop in concentration might just mean the treatment is a little less effective. For an NTI drug, that same drop could trigger a seizure or cause your blood to clot uncontrollably.

Common NTI drugs include warfarin (blood thinner), phenytoin and levetiracetam (anti-seizure meds), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), digoxin (heart medication), cyclosporine and tacrolimus (transplant drugs), and amiodarone (heart rhythm control). These aren’t obscure pills - they’re life-sustaining for millions. Warfarin alone is prescribed to nearly half of all NTI patients. Levothyroxine comes in second. These aren’t edge cases. They’re central to daily health for people with chronic conditions.

Generic Substitution: The Regulatory Gap

The FDA allows generic drugs to be approved if they’re within 80% to 125% of the brand-name drug’s absorption rate. That’s called bioequivalence. Sounds fair? Not for NTI drugs. A 125% absorption rate means your body gets 25% more of the drug than intended. For warfarin, that could mean a dangerous spike in bleeding risk. For cyclosporine, it could trigger organ rejection. For phenytoin, it could cause toxicity like tremors, confusion, or even coma.

Other countries know this. Canada and the European Medicines Agency require a much tighter range: 90% to 111% for NTI drugs. That’s a 21% narrower window than what the FDA accepts. Why? Because studies show that switching between generics that hit the FDA’s upper and lower limits could expose a patient to more than a 50% difference in total drug exposure over time. Imagine switching from one generic to another - both approved - and suddenly your blood levels jump from safe to toxic. That’s not hypothetical. It’s documented.

Warfarin: Mixed Signals, But Monitoring Works

Warfarin is the most studied NTI drug. It’s also the most commonly switched. One study of 36,911 patients found nearly half started on a generic version. That’s high adoption. But what happened after the switch?

Observational data shows trouble. One study found only 28% of patients stayed within 10% of their target INR (a measure of blood clotting) after switching to a generic. Nearly 39% had worse control. That means more trips to the clinic, more blood tests, more risk of stroke or bleeding.

But here’s the twist: randomized controlled trials - the gold standard - found no significant difference in bleeding or clotting events between brand and generic warfarin. So which is right? The answer might be in the details. Real-world patients aren’t in controlled labs. They’re juggling other meds, changing diets, skipping doses. Generic switches add another variable. The fix? More monitoring. The AMA and FDA both say: if you switch warfarin, check INR within 3 to 7 days, then again at 2 and 4 weeks. Done right, most patients stabilize. Done wrong, it’s dangerous.

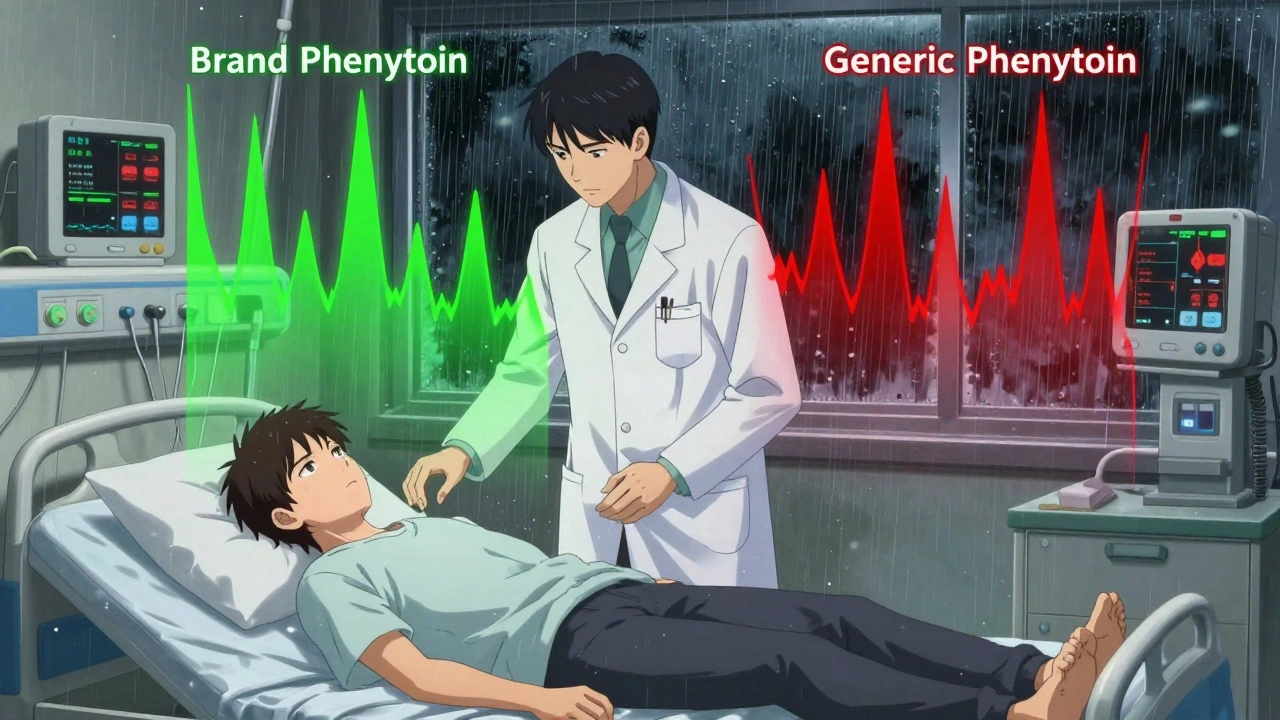

Antiepileptic Drugs: The Real Danger Zone

If warfarin is risky, antiepileptic drugs like phenytoin and levetiracetam are a minefield. For epilepsy patients, a seizure isn’t just inconvenient - it’s life-threatening. And even a small drop in drug levels can trigger one.

A review of 760 patients found that switching to generic levetiracetam led to increased seizures, blurred vision, depression, memory loss, and aggression. Many had to switch back to the brand. In another study, patients on generic phenytoin had 22% to 31% lower blood levels than when on the brand. Nearly half of those who had breakthrough seizures had lower drug levels at the time. One physician survey documented 50 patients who had seizures after a generic switch - and nearly half of them had confirmed lower serum levels.

That’s why 73% of U.S. states have laws that require pharmacists to get explicit permission from the doctor before substituting generic antiepileptics. It’s not about distrust - it’s about survival. Neurologists often refuse to switch patients who are seizure-free. Why risk it?

Immunosuppressants: The Transplant Tightrope

For transplant patients, cyclosporine and tacrolimus aren’t just medications - they’re the barrier between life and rejection. A drop in levels? The body attacks the new organ. A spike? Toxicity, kidney damage, infection.

One study followed 73 patients who switched from Neoral (brand) to a generic cyclosporine. Within two weeks, 17.8% needed a dosage adjustment. Their drug levels jumped from an average of 234 ng/mL to 289 ng/mL. That’s a 23% increase - outside the safe range for many. None of the control group (those who stayed on brand) needed changes.

Tacrolimus has slightly better data. Some studies show bioequivalence under tighter standards. But here’s the catch: different generic manufacturers vary wildly. One study found active ingredient levels ranged from 86% to 120% across four different generic brands. That means switching from one generic to another - even without touching the brand - could send levels soaring or crashing. Transplant centers now routinely check drug levels at 2 and 4 weeks after any switch. No exceptions.

What Patients Are Saying

Behind the numbers are real people. On Reddit’s r/transplant, users describe rejection episodes after switching from Neoral to generic cyclosporine. Others say they’ve been fine for five years. On epilepsy forums, patients recount sudden seizures after switching to generic levetiracetam. One thread lists 37 cases. On PatientsLikeMe, 42% of warfarin users reported unstable INR after a generic switch. But 58% didn’t notice a difference.

That’s the pattern: some people are fine. Others aren’t. And you can’t predict who’s who. The risk isn’t evenly distributed. It’s personal. It’s biological. It’s tied to metabolism, age, other meds, even diet. That’s why blanket policies fail.

What Pharmacists and Doctors Are Doing

A national survey of 710 pharmacists found 82% would still substitute generic NTI drugs. But 41% recommended extra monitoring - and 62% specifically worried about antiepileptics. That’s a disconnect. They know the risks, but they’re under pressure to cut costs.

Doctors are more cautious. Many avoid switching patients who are stable. Others require written consent. Some use therapeutic drug monitoring as standard practice after any switch. The FDA’s official stance is that AB-rated generics are equivalent - but they also admit NTI drugs need tighter standards. In 2022, they started drafting product-specific bioequivalence guidelines for NTI drugs, moving away from the one-size-fits-all approach.

The Bottom Line: When to Switch, When Not To

Is it safe to switch? Sometimes. But not without caution. Here’s what the evidence says:

- For warfarin: Switching is possible with close INR checks at days 3, 7, 14, and 28. Most patients stabilize. But don’t assume it’s automatic.

- For antiepileptics: Avoid switching if you’re seizure-free. If you must, do it under direct neurologist supervision with blood level checks.

- For transplant drugs: Never switch without checking trough levels at 2 and 4 weeks. Any change = new monitoring protocol.

- For levothyroxine: Even small changes in formulation can affect TSH levels. Many endocrinologists recommend sticking to the same brand or generic - and checking TSH 6 weeks after any switch.

There’s no universal answer. What works for one person may harm another. The goal isn’t to ban generics - it’s to handle them with the care they demand. Cost savings matter. But not at the cost of safety.

What’s Next?

The future of NTI drug management is personalization. Research is underway to use genetic testing to predict how a patient metabolizes drugs like warfarin or phenytoin. That could tell you upfront whether a switch is safe for you. Until then, the best tool is vigilance: know your drug, track your levels, and speak up if something feels off.

Generic drugs saved billions. But NTI drugs aren’t commodities. They’re precision tools. Treat them that way.

Are all generic NTI drugs the same?

No. Different manufacturers produce generics with varying inactive ingredients, dissolution rates, and active ingredient concentrations. Studies show some generics vary by up to 34% in active drug content. Switching between different generic brands - even after switching from brand to generic - can cause dangerous fluctuations in blood levels.

Can I switch back to the brand if I have problems?

Yes, and you should. If you notice new symptoms - more seizures, unusual bruising, fatigue, or mood changes - after a generic switch, contact your doctor immediately. Most insurance plans will cover a brand-name drug if your doctor documents therapeutic failure or adverse effects from the generic. Don’t wait for a crisis.

Why do some countries have stricter rules for NTI generics?

Because their studies showed harm. Canada and the EU saw higher rates of adverse events and therapeutic failures after generic switches for drugs like warfarin and cyclosporine. They tightened the bioequivalence range to 90-111% to reduce the risk of dangerous blood level swings. The U.S. still uses the broader 80-125% range, despite evidence that it’s too loose for these high-risk drugs.

Should I ask my doctor before a generic switch?

Always. For NTI drugs, you should never assume a switch is automatic. Ask: "Is this switch safe for me? Will I need extra blood tests? What signs should I watch for?" If your doctor says "it’s fine," ask for the evidence. For drugs like phenytoin or cyclosporine, a simple conversation can prevent hospitalization.

Do pharmacists know which NTI drugs are risky?

Many do, but not all. A survey found that while 87% of pharmacists believe generics are equally safe, nearly half still recommend extra monitoring for NTI drugs. Pharmacists in independent pharmacies are more likely to flag concerns than those in large chains. Always ask your pharmacist: "Is this a high-risk generic? Should I get my levels checked?" Don’t assume they know your full history.

olive ashley

December 5, 2025 AT 20:08So let me get this straight - the FDA lets drug companies slide with 80-125% bioequivalence for life-or-death meds, but if you switch your toilet paper brand, they send a compliance team? This isn't healthcare. It's corporate roulette with your organs as the prize.

My aunt died after a generic cyclosporine switch. They called it 'natural progression.' I call it negligence dressed up as cost-cutting.

They don't care. They're making billions off the brand, then outsourcing the risk to people who can't afford the name. Wake up.

And don't even get me started on how pharmacists are pressured to switch without telling you. I found out my warfarin changed because I checked the pill color myself. No one warned me.

This system is rigged. And you're the one paying the price in blood tests, seizures, and funeral bills.

Dan Cole

December 6, 2025 AT 12:09Let’s dismantle this fallacy with epistemological rigor. The FDA’s 80–125% bioequivalence standard is not an oversight - it is a philosophical compromise between utilitarian public health policy and the metaphysical illusion of pharmaceutical uniformity.

Drugs are not widgets. They are dynamic molecular ecosystems interacting with uniquely variable human biologies. To treat them as interchangeable commodities is to commit the reification fallacy - mistaking the map for the territory.

Canada and the EU enforce tighter ranges not because they’re morally superior, but because their healthcare systems are centralized enough to absorb the cost of vigilance. America’s fragmented system outsources risk to patients - and that’s not a flaw, it’s a feature of capitalism’s Darwinian design.

Meanwhile, the AMA’s INR monitoring protocol? A bandage on a severed artery. We need pharmacogenomic stratification, not reactive blood draws. Until then, we’re all lab rats in a rigged experiment.

And yes - I’ve read every study. You haven’t.

Billy Schimmel

December 7, 2025 AT 13:31Man, I just read this whole thing and felt like I needed a nap.

I get it - switching meds can be scary. But I’ve been on generic levothyroxine for 8 years. No issues. My TSH is perfect.

Maybe the problem isn’t the generic - maybe it’s the panic.

My grandma switched her warfarin and lived to 92. She didn’t check her INR every week. She just took her pill and went to bingo.

Not everyone’s a ticking time bomb. Some of us just… live.

Also, I’m pretty sure the FDA isn’t trying to kill us. Just trying to make pills cheaper. You’re welcome, America.

Inna Borovik

December 7, 2025 AT 13:38Oh, here we go again - the ‘NTI drug panic’ narrative. Let’s look at the data, shall we? The 2019 JAMA study of 42,000 warfarin patients showed no statistically significant increase in hemorrhage or thrombosis after generic switch.

Meanwhile, the 760-patient levetiracetam review? Retrospective. Confounding variables everywhere - noncompliance, alcohol use, sleep deprivation. You can’t pin seizures on a pill change without ruling out the other 17 variables.

And yes, some generics vary. So do brand-name batches. Ever heard of batch-to-batch variation? The FDA doesn’t test every pill. They test samples. Same for everyone.

Stop treating patients like fragile glass animals. They’re people. They adapt. And if they don’t? Switch back. It’s not rocket science.

Also - your doctor isn’t a pawn. They’re trained. Trust them. Or get a second opinion. But don’t turn a pharmacology lecture into a horror story.

Rashmi Gupta

December 9, 2025 AT 12:22USA thinks it’s the center of the medical universe. But the rest of the world? They’ve known for decades that your 80–125% range is a joke.

India makes 40% of the world’s generics. We’ve seen what happens when you don’t regulate. People die. Not in studies. In villages. In hospitals with no labs.

You want to know why the EU tightened standards? Because they didn’t wait for a PR crisis. They acted.

Meanwhile, your FDA? Still letting companies use cornstarch fillers that change absorption based on humidity. And you wonder why your blood levels swing like a pendulum?

Stop pretending this is about science. It’s about profit. And you’re the sucker paying for it.

Andrew Frazier

December 11, 2025 AT 00:13Y’all act like generics are some foreign conspiracy. Let me tell you something - America built the best damn pharmaceutical industry in the world. And now you wanna throw it away because some Canadian professor got scared?

My cousin took generic cyclosporine after his transplant. He’s alive. He’s working. He’s got a kid now.

Meanwhile, you’re out here crying about 23% absorption differences like it’s the end of the world. Get a grip.

If you can’t afford your meds, that’s your problem. Not the system’s. We don’t hand out gold-plated pills here. We make medicine that works - cheaper.

Stop whining. And stop letting Europe tell us how to run our health system. We don’t need your 90–111% rules. We’ve got common sense.

Mayur Panchamia

December 12, 2025 AT 13:39Ha! You think this is about safety? Nah. This is about CORPORATE GREED disguised as PATIENT CARE!

Brand-name companies? They’re the ones lobbying the FDA to keep the 80–125% loophole open! They don’t want you to know that their own generics - yes, the ones they manufacture - vary more than the ‘rival’ generics!

And guess who profits when you get a seizure? The ER. The ICU. The insurance company that denies your claim because it’s a ‘pre-existing condition’.

Meanwhile, the Indian and Chinese factories? They’re making pills that cost 2 cents to produce - and selling them for $12. You think they care if you bleed out?

This isn’t science. It’s a $300 BILLION racket. And you’re the mark.

Also - I’ve seen the lab reports. The differences? 34%? That’s not bioequivalence. That’s a fucking lottery ticket.

Karen Mitchell

December 14, 2025 AT 00:47It is deeply troubling that a society which prides itself on individual liberty permits the wholesale substitution of life-sustaining pharmaceuticals without informed, written, and notarized consent.

One cannot ethically justify the commodification of biological stability under the banner of fiscal efficiency.

Moreover, the FDA’s continued refusal to adopt the European model - despite overwhelming clinical evidence - constitutes a dereliction of its statutory duty to ensure safety and efficacy.

One wonders: when the first child dies from a generic levetiracetam switch, will the regulators weep? Or will they issue a press release about ‘statistical insignificance’?

This is not a debate. It is a moral failure.

Nava Jothy

December 15, 2025 AT 12:47I’ve been on generic levothyroxine for 3 years… and I cry every night. Not because of the meds. Because I’m so tired of people saying ‘it’s fine’.

My TSH went from 2.1 to 7.8 after a switch. I gained 20 pounds. My hair fell out. My husband left me.

I went to 12 doctors. They all said ‘it’s just the generic’. But I knew. I felt it.

Now I pay $200/month for Synthroid. My insurance hates me. My pharmacist rolls her eyes.

But I’m alive. And my hair is growing back.

So yeah. It’s not ‘just a pill’. It’s my soul. And I’m not letting them take it for $10 cheaper.

💔😭

brenda olvera

December 16, 2025 AT 14:06Hey everyone - I’m from Mexico City but living in Texas now. I work at a pharmacy and I see this every day.

People are scared. They shouldn’t be. Most switches are fine.

My mom takes generic warfarin. She’s 72. She walks 3 miles a day. No problems.

But I always ask: ‘Have you been feeling different?’ If yes? We call the doctor.

It’s not about brand vs generic. It’s about listening.

And yes - I tell patients to check their pill color. If it’s different, ask. No shame.

We’re not enemies. We’re just trying to help.

Love y’all. Stay safe.

- Brenda 💛

Ibrahim Yakubu

December 18, 2025 AT 05:53Y’all in America think you’re the only ones with NTI drugs? In Nigeria, we don’t even have access to generics. We get expired pills from Europe. Some are labeled ‘for veterinary use’.

So you’re complaining about a 25% absorption difference? Try getting 10% of the dose. Or none at all.

My cousin died from epilepsy because the only ‘generic’ available was crushed aspirin with chalk.

Stop comparing your first-world problems to ours.

Yes, the FDA is flawed. But at least you have a system. We have a lottery.

And no - we don’t have Reddit to scream into. We just pray.

Chris Park

December 19, 2025 AT 23:54Let’s be clear: the FDA doesn’t care if you die. They care about stock prices.

Every time a generic manufacturer files an ANDA, they pay a fee. The FDA gets paid. The drugmaker gets approval. The patient? An afterthought.

And the worst part? The same companies that make the brand? They also make the ‘generic’. Same factory. Same machine. Just a different label.

So when you say ‘the generic is different’ - you’re lying to yourself.

It’s the same pill. But now you’re paying less. And the FDA lets them change the filler. That’s it.

So why do some people have seizures? Because their bodies are different. Not because the pill is bad.

It’s biology. Not corruption.

Stop blaming the system. Start understanding your own body.

Priya Ranjan

December 20, 2025 AT 03:38Let’s be honest - if you’re the type of person who needs to know the exact absorption rate of your levetiracetam, you probably shouldn’t be left unsupervised with a knife, a microwave, and a smartphone.

Most people take their meds. They live. They don’t die. The outliers? They’re outliers.

Why are we treating 1% of cases as the new normal?

Also - if you’re worried about your INR, why aren’t you getting checked every week? You’re not a patient. You’re a hypochondriac with a lab report.

And yes - I’ve seen the data. The risk is lower than being hit by lightning.

Stop turning medicine into a horror movie.

Also - your doctor knows more than you think.

Gwyneth Agnes

December 20, 2025 AT 16:17Switch back if it doesn’t feel right.

That’s it.

No drama.

No conspiracy.

Just do it.

Billy Schimmel

December 21, 2025 AT 16:58Actually, Brenda - your comment made me feel better.

I was freaking out after switching my levothyroxine. Thought I was dying.

Turned out I just needed to take it on an empty stomach. Like the bottle said.

Turns out I’m the dumb one.

Thanks for not being a doomscrolling robot.

Now I’m going to eat breakfast and stop Googling ‘generic thyroid death’.